By Hadleyblogger Drew

Finally, Riefenstahl.

Finally, Riefenstahl.

It's been so long since I started this thread that's it's difficult to recall what the point of it all was supposed to be. (And I'm glad I haven't been kicked off the blog for being so late in getting this up!)

But this whole discussion started with the death of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf last month. As was mentioned back then, virtually every obit of the great opera star mentioned her past association with the Nazi party in WW2 Germany. And I supposed it's a natural segueway, once you've talked about Schwarzkopf, to look at the lives of two other prominent German artists: Leni Riefenstahl and Richard Wagner. (Günter Grass doesn't really count, since he wasn't part of my original plan and, anyway, I've already talked about him enough.)

And in looking at their lives, we continue to be drawn to the central question of the discussion: what is the relationship between the artist and the art? As Roger Ebert has noted, it raises the “classic question of the contest between art and morality: Is there such a thing as pure art, or does all art make a political statement?"

Leni Riefenstahl was one of the great film documentarians of the 20th century. From Wikipedia: (I'll quote liberally here, since I have no desire to get this blog tied up in a plagerism accusation:

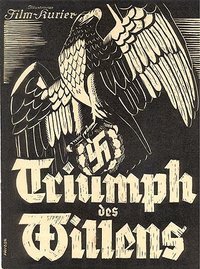

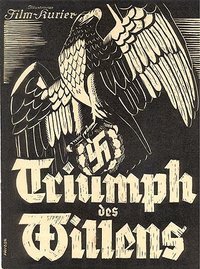

Riefenstahl's techniques, such as moving cameras, the use of telephoto lenses to create a distorted perspective, aerial photography, and revolutionary approach to the use of music and cinematography, have earned Triumph recognition as one of the greatest propaganda films in history. [...] The film was popular in the Third Reich and elsewhere, and has continued to influence movies, documentaries, and commercials to this day, even as it raises the question over the dividing line between "art and morality."

But, as you might have gathered from the above paragraph, there’s that Nazi thing again. Of all Riefenstahl's documentaries, none is perhaps as famous - and infamous - as Triumph of the Will. It is a magnificent, terrible film of a horrible story - the Nazis and their Nuremberg rallies during the '30s. And in telling that horrible story, it also ensured that filmmaking would never be the same again.

Film historians have seen Riefenstahl's influence in movies ever since. Star Wars, Citizen Kane, Gladiator, Lord of the Rings - all bear the marks of Riefenstahl's style. The famous opening scene of Triumph, in which the camera moves through the clouds to capture an aerial shot of the city of Nuremberg (to the music of Wagner, naturally) must have influenced Wim Wenders' opening of Wings of Desire. The sports documentarian Bud Greenspan, one of the finest filmmakers of the 20th century (Ken Burns could take a chapter from him), considers her one of the greats.

It's an assertion few would dispute, in the academic sense. But can’t you detect just the smallest bit of embarrassment whenever one praises the work of Riefenstahl? True, Triumph of the Will is a staple of many “best all-time” lists, but there’s this sense that even when we praise Riefenstahl, we must immediately apologize or explain away the praise, lest we fall under guilt-by-association. The closer we get to her work, the more we edge away from it. It’s not likely you’d hear Seinfeld emerge from the theatre saying, “It’s about Nazis! Not that there’s anything wrong with that.” (Warning: Do not insert any Soup Nazi jokes here.)

No, you’ll never hear anyone say there’s nothing wrong with being a Nazi. In our time the Nazi brand is, as I've said before, the Scarlet Swastika, an accusation so accursed that its use has become widespread, indiscriminate, a self-parody. And yet it is a charge that carries power, a negative sort of prestige, a stigma that taints whatever it touches. And we ask ourselves if we should be ashamed by our admiration and praise of the artist’s work, if we can morally separate the ideology of the artist from the art itself.

No, you’ll never hear anyone say there’s nothing wrong with being a Nazi. In our time the Nazi brand is, as I've said before, the Scarlet Swastika, an accusation so accursed that its use has become widespread, indiscriminate, a self-parody. And yet it is a charge that carries power, a negative sort of prestige, a stigma that taints whatever it touches. And we ask ourselves if we should be ashamed by our admiration and praise of the artist’s work, if we can morally separate the ideology of the artist from the art itself.

Riefenstahl’s work does not allow us that luxury. The subject matter of Triumph of the Will is in your face, and you can't ignore it. As the Wikipedia bio puts it, "it is nearly impossible to separate the subject from the artist behind it." She “claimed that she was naïve about the Nazis when she made it and had no knowledge of Hitler's genocidal policies. She also pointed out that Triumph contains ‘not one single anti-Semitic word’“; but it is difficult (although not impossible) to conceive of her as both ingénue and naïve girl, the brilliant and innovative filmmaker who was still a babe in the woods when it came to world politics. This is what she would have liked you to believe, but her actions often belie that contention. Roger Ebert points out, "the very absence of anti-Semitism in Triumph of the Will looks like a calculation; excluding the central motif of almost all of Hitler's public speeches must have been a deliberate decision to make the film more efficient as propaganda." And so, given all this, we’re tempted to see in her films things that aren’t really there, images that dance before us like the ghosts from black & white TV. Only these are real, the ghosts of Hitler’s victims that only become clearer as the picture is drawn into sharper focus.

Therefore, as viewers do we punish the filmmaker because of the subject of her films? Do we hold Riefenstahl accountable for her Nazi associations? And if so, do we also apply the same standards to Sergei Eisenstein, who exploited Russian nationalistic pride in Potemkin and Alexander Nevsky? (Yes, I know Eisenstein had his quarrels with the authorities, but large families often do that.) Eisenstein is often ranked in the pantheon of filmmaking, Potemkin appearing on most ten-best lists, but I rarely see him carrying around the baggage that accompanies Riefenstahl. And we won't even get into the almost-paranoid, conspiracy-laden propaganda of liberal filmmakers like Oliver Stone?

Now, it's true that Eisenstein wasn't a documentarian as was Riefenstahl. Nonetheless, his movies were fraught with nationalistic fervor, clearly designed to influence and inspire the viewer. (The Communists, in fact, thought Eisenstein worried too much about things like art and budgeting, and wanted even more propaganda in the content.) As for Stone - well, we know most of his films have an agenda.

Some like to pair up Triumph of the Will with Frank Capra’s direct answer to them, the Why We  Fight series of films. (And, by the way, given how anti-American Hollywood has become, it would have been interesting to see how Capra's reputation might have suffered had he been young enough when he made this series. Surely in the Hollywood of the late 60s through today, he would have been seen as a toady for the government.)

Fight series of films. (And, by the way, given how anti-American Hollywood has become, it would have been interesting to see how Capra's reputation might have suffered had he been young enough when he made this series. Surely in the Hollywood of the late 60s through today, he would have been seen as a toady for the government.)

In fact, however, the true companion to Riefenstahl’s masterwork might be D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. This truly was a landmark of filmmaking, but most today remember it only as a racist piece of propaganda, glorifying the Ku Klux Klan. True, perhaps, but Griffith's influence, like Riefenstahl's, cannot be denied. True also that Griffith, like Riefenstahl, is held at arms' length by most.

So what's the point here? It's not an apology for Leni Riefenstahl (or D.W. Griffith, for that matter). It's merely an observation on how we allow our politics to color the way we see things. As I've asserted in the past, it is hard to believe that Riefensthal would be held in such contempt had the Triumph in question been Lenin's October Revolution.

As we watch the ridiculous accusations of Nazism that are so commonplace nowadays across the political blogosphere, and perhaps most absurdly from the Muslims who brand the Jews with the contemptuous tag, we are reminded that Nazism is the singular golden sin, the mark from which its bearers cannot recover. It is reminiscent of the "unforgivable sin" that Christ warns us of, though most of those wielding it would fail to recognize that analogy since they don't recognize the source.

National Socialism keeps us in a trance, as perhaps it should. It holds the figures of history hostage, as perhaps it might. But we do not diminish the horror of the truth it represents to assert also that the word "Nazi" is the crown jewel of political correctness, the golden spike to be driven through the heart, the one word that guarantees the discrediting of its intended. Some would wear the title as a badge of honor, an ideology to be embraced, others are shamed with a scarlet letter and their lips burn with Judas' kiss of betrayal, and still others feel the sting of its indiscriminant application.

But while Schwarzkopf shrugged off the label, and Riefenstahl tried to run from it, Richard Wagner might have welcomed it with open arms. But that's for another time.